January 19, 2023

By Stephen Gowans

….peace must be sought for and fought for, not in … a reactionary utopia of a non-imperialist capitalism, not in a league of equal nations under capitalism, but in the future, in the socialist revolution of the proletariat. — Lenin, The Peace Program, 1916

Abstract

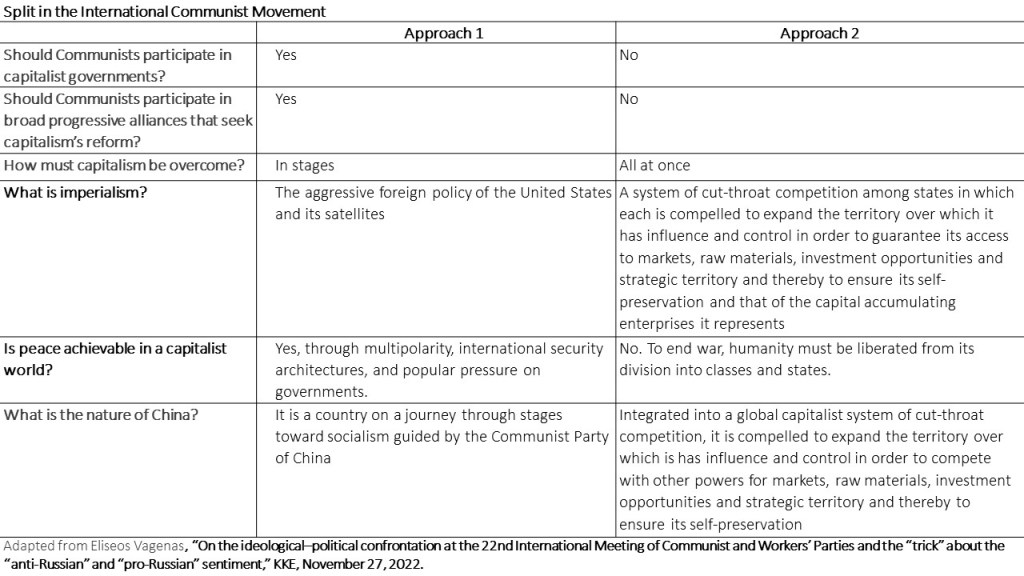

Two years after Russia annexed Crimea, Radhika Desai, Alan Freeman and Boris Kagarlitsky argued in “The Conflict in Ukraine and Contemporary Imperialism” that while the term imperialism continued to be an appropriate description of the pattern of Western actions, it was not so for that of Russian ones. In their paper, the trio drew on thinking about imperialism that comported with the views of Rudolph Hilferding and Nicolai Bukharan, popularized by V.I. Lenin, that imperialism is competition among capitalist states to impose their respective wills on other territories and populations in response to the needs of their capitalist class. However, they abandoned this thinking when they set out to answer the question: Is Russia imperialist? Rather than following the Hilferding-Bukharin view to its logical end, an exercise that would have identified Russia as a participant in a system of rivalry among capitalist states for economic territory, they constructed a scale of capitalist powers from weakest to strongest and then drew an arbitrary dividing line to separate imperialist capitalist states from a class of non-imperialist ones, which included Russia. The approach, based on the Texas sharpshooter fallacy, conformed to no external standard, except the authors’ acknowledged desire to arrive at a characterization of Russia that avoided demonizing Moscow or giving “theoretical dignity to the ambitions of US-policy makers.” In doing so, the authors went to the opposite extreme of offering an understanding of the world that dovetailed nicely with Russia’s denial of its imperialist aims and gave theoretical dignity to the ambitions of Russian-policy makers. The role of Marxist scholars is not to act as court philosophers for one bourgeoisie in its confrontation with another, as Desai and her coauthors did, but, as Lenin argued, to assist in the project of using the struggle between competing capitalist classes to overthrow all of them.

Radhika Desai, Alan Freeman and Boris Kagarlitsky wrote “The Conflict in Ukraine and Contemporary Imperialism,” [1] in 2016, before Russia, with the aim of installing a puppet government in Kyiv, invaded Ukraine, but after Moscow annexed Crimea. Their intention was to argue that the latter event did not mark Russia as an imperialist aggressor.

While a major aim of their paper was to show that Russia cannot be characterized as imperialist, at no point did the authors define imperialism. While they offered brief, superficial sketches of various Marxist theories of imperialism, they did not commit to any definition of the phenomenon, but all the same, a broad definition lurked within some of their arguments. Their failure to provide a clear definition of imperialism at the outset of their paper was highly problematic.

The word imperialism means different things to different people. Marx and Engels used it to refer to the spread of capitalism to non-capitalist territories. Because they regarded capitalism as the bridge to socialism, and progressive relative to less dynamic modes of production, they viewed imperialism favorably. Speaking of Britain’s role in India, Marx remarked that “whatever may have been the crimes of England she was the unconscious tool of history,” for she established in India the preconditions for an advance to socialism. [2]

This contrasts with the way imperialism is understood today. As Bill Warren argued in Imperialism: Pioneer of Capitalism, “Current popular usage has tended to equate modern imperialism with the prevailing relationships of domination and exploitation between advanced capitalist and underdeveloped economies.” [3]

Echoing Warren, John Weeks noted that,

“The most common use of the term is in narrow reference to the economic and political relationship between advanced capitalist countries and backward countries. Since the second world war the word imperialism has become synonymous with the oppression and exploitation of weak, impoverished countries by powerful ones.” [4]

While the current understanding is similar to that of Marx and Engels in emphasizing the relationship between the metropole and periphery, it is different in condemning imperialism where Marx and Engels welcomed it (even if they did acknowledge its crimes.) “Many of the writers who present such an interpretation cite Lenin as a theoretical authority,” noted Weeks, while pointing out that this view is traceable to Karl Kautsky and not Lenin who, in fact, vehemently opposed it. [5]

Rudolph Hilferding, Nicolai Bukharan, and VI Lenin viewed imperialism as a system of rivalry among capitalist powers for economic territory. In their account, the world had been completely divided into colonies and spheres of influence, and the only way capitalist powers could expand under the lash of the capitalist compulsion for accumulation was to encroach on the economic space of other powers. That space included not only the territory of agrarian states, but the national territory of industrialized powers themselves.

In contrast, Kautsky argued that advanced capitalist states might give up competition for cooperation in exploiting the periphery. Imperialism, understood at the time as rivalry among capitalist states, would be succeeded by ultra-imperialism, a common front of capitalist states against the periphery. It is surely this view of imperialism—in contemporary terms, one of G7 countries, led by the United States, jointly enslaving and exploiting the rest of the world—that is generally understood by the term ‘imperialism’ today. [6] In Lenin’s time, the very suggestion that capitalist states could settle into a Kautsky-style ultra-imperialism aroused vehement hostility from the left.” For Lenin and his colleagues, including Stalin, who railed against this view as late as 1952 [7] “inter-imperialist rivalry leading to war was the very essence of imperialism.” [8] Thus, while many Marxists often cite Lenin as the source of the idea that imperialism is the exploitation of the periphery by metropolitan powers, “Lenin sharply criticized Kautsky for defining imperialism in this way.” [9] As Lenin argued,

“The characteristic feature of imperialism is precisely that it strives to annex not only agricultural regions but even highly industrialized regions, because (1) the fact that the world is already divided up obliges those contemplating a new division to reach out for any kind of territory, and (2) because an essential feature of imperialism is the rivalry between a number of great powers in the striving for hegemony, i.e., for the conquest of territory.” [10]

Russian propagandists allude to the current understanding of imperialism as Kautsky’s ultra-imperialism when they invoke the concept of the “golden billion,” a reference to a US-led alliance of high-income countries representing a population of roughly one billion of the world’s total population of eight billion people, who are presented as jointly oppressing the remaining seven-eighths of humanity. The view also lurks in the concept of multipolarity, the idea that the poorest seven-eighths of humanity, led by China and Russia, is rising to contest the hegemony of G7 ultra-imperialism. The multipolarity theory casts Russia and China, not as capitalist powers that compete with G7 states for economic territory, driven by the needs of their own capitalist classes, but as leaders of a great movement of emancipation against Western ultra-imperialism. The argument resurrects the theory advanced by Tokyo in the 1930s that Japan’s competition with the United States, Great Britain, France, and the Netherlands for economic territory in East Asia and the Pacific, represented, not Lenin’s view of inter-imperialist rivalry, but Japan leading the East to challenge its thralldom to the ultra-imperialism of the West. At the same time, it should be noted that the idea of the “golden billion” and the theory of multipolarity significantly depart from Kautsky’s ultra-imperialism in arbitrarily counterposing China and Russia and other emerging capitalist states against the G7, as Japan in the 1930s, a significant capitalist state, counterposed itself against Western capitalism. From Kautsky’s perspective, we would expect that Russia and China, as significant capitalist states, would combine with their North American, European, and Japanese counterparts to jointly oppress the periphery, rather than compete against G7 states. Instead, exponents of the “golden billion” and multipolarity views portray capitalist Russia and capitalist China as imperialist Japan portrayed itself in the 1930s—as champions of peoples oppressed by an ultra-imperialist coalition of US-led bourgeois states.

Other Marxists, citing Lenin, understand imperialism as a stage of capitalism, specifically its monopoly stage, in contrast to what Lenin understood as a non-imperialist period of free competition preceding it. To these Marxists, imperialism is a system of rivalry among capitalist states, rather than a set of characteristics that distinguish imperialist states from non-imperialist ones. They make the argument that when Lenin presented his now famous list of five imperialist characteristics in Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism, written in 1917, that his intention was to describe the landscape of the latest stage of capitalism, not to propose a set of criteria by which to distinguish capitalist imperialist states from capitalist non-imperialist states. Indeed, it is abundantly evident in an earlier (and more clearly written) 1915 version of the now widely misinterpreted list that Lenin had in mind the features of a system.

The present war is of an imperialist character. This war is the outcome of the conditions of an epoch when capitalism has reached the highest stage of its development; when the greatest significance is attached not only to the export of commodities, but also to the export of capital; when the combination of production units in cartels, and the internationalization of economic life, has assumed considerable dimensions; when colonial politics have brought about an almost total apportionment of the globe among the colonial powers; when the productive forces of world capitalism have outgrown the limited boundaries of national and state divisions; when objective conditions for the realization of Socialism have perfectly ripened. [11]

There is no doubt that Lenin is describing “the conditions of an epoch,” not the characteristics of individual countries. He is not, for example, saying that countries that export more commodities than capital are not imperialist, as some people believe.

If the epoch is imperialist, is the concept of a non-imperialist capitalist state even admissable in Lenin’s view? Lenin saw the world economy as an integrated system, a network of interrelationships in which all states are entangled. The monopoly character of the system compels its capitalist states to compete for raw materials, markets, investment opportunities, and strategic territory. The competition creates multiple frictions that tend to escalate to war. There are no exemptions—no capitalist states which are not driven to expand their economic territory; no capitalist states which operate above or outside the competitive fray. Some states thrive in the competition while others are out-competed and fail, but those that fail have not elected to sit out the competition as pacific, non-imperialist states; they’ve just been bested by stronger states.

None of this is to endorse every aspect of Lenin’s theory. There is much about it that is problematic, including the fact that it’s not even his theory. Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism, which many Marxists revere as Lenin’s masterwork on the subject, is only a “popular outline” of Hilferding’s Finance Capital and Bukharin’s Imperialism and World Economy, supplemented with ideas from John Hobson’s 1902 book Imperialism: A Study. Lenin’s unique contribution to the theory of imperialism was to develop a theory of the labor aristocracy and to link it to the rise of monopoly capitalism as a means of explaining the Second International’s betrayal of socialist internationalism in the First World War.

In considering Lenin’s popular outline of Hilferding’s, Bukharin’s, and Hobson’s thinking, it’s important to draw two sets of distinctions. The first is between imperialism as a phenomenon and theories of imperialism as explanations of the phenomenon. When we say “Lenin defined imperialism as the monopoly stage of capitalism” we confuse Lenin’s explanation of imperialism with his definition of it. Lenin wasn’t saying that imperialism is the monopoly stage of capitalism, only that monopoly explains the scramble for colonies that he believed was coincident with and driven by the emergence of monopoly. This then invites the question of exactly what phenomenon Lenin, or more precisely, Hilferding and Bukharin, were trying to explain. The answer is the intense competition among capitalist powers for economic territory that emerged with the scramble for Africa and continued into the conflagration of World War I.

The second important distinction to draw is between motive and means. A theory of imperialism should specify both the cause of the phenomenon, and how it’s carried out. It is clear in the Hilferding-Bukharin view, as outlined by Lenin, that the motive of imperialism is economic territory, to be acquired in competition with other capitalist states. The theory stumbles, however, in failing to recognize that the means by which capitalist powers integrate economic territory into their national economies is not limited to formal annexation. Gallagher and Robinson, in their article “The Imperialism of Free Trade” [12] and later in Africa and the Victorians: The Official Mind of Imperialism [13] showed how Britain built its vast empire less by coercion and annexation and more by finding willing collaborators to collude in the integration of territories into the expanding British economy. The historians likened the British empire to an iceberg. If one looked only at the part that was visible above the surface, as they said Lenin had done, one would miss its true dimensions, the bulk of which lies below the surface and is invisible. The history of the British empire had shown that informal means of extending imperial supremacy have been preferred to direct rule. The guiding principle was: informal control, if possible; formal control, only if necessary.

Jo Grady and Chris Grocott have used the insights of Gallagher and Robinson to explore how the United States has used both formal and mainly informal methods of control to build and maintain its own empire. [14] Based on the work of Gallagher and Robinson, they argue that the break Lenin saw between a non-imperialist period of free competition and a subsequent imperialist stage of monopoly capitalism was actually a transition from an imperialist period in which mainly informal methods of control were used (and thus the imperialist character of the period was difficult to discern) and a period in which methods of formal control became necessary (and imperialism, expressed mainly in formal annexation and colonialism, became easier to see.) Formal control became necessary at about the time Hilferding, Bukharin and Lenin said that capitalism had entered a new monopoly stage. Dominated populations were beginning to bristle under the weight of informal control exercised from abroad and capitalist states were beginning to expand into territory in which willing collaborators, who could impose informal methods of control, were difficult to find. Before capitalism reached its monopoly phase, capitalist states had relied heavily on European settler populations as the willing collaborators who would integrate foreign territory into expanding metropolitan economies. Increasingly, however, the territories not yet claimed by expanding capitalist states, in Africa mainly, were ill-suited to European settlement. Willing collaborators accepted capitalist values and institutions and were keen to trade with the metropolitan centers. But these values, institutions, and this desire were alien to indigenous populations. As a consequence, formal control, though undesired, became necessary as the only feasible alternative to integrating the remaining territories of the world into expanding capitalist economies. Completing the division of the world would thus depend on the increasing use of violence.

This points out a weakness of the Hilferding-Bukharin-Lenin view. According to these theorists, two crucial things happened in the late nineteenth century. “The territorial division of the whole world among the greatest capitalist powers” was completed, as Lenin observed in Imperialism. And capitalism entered a new stage, that of monopoly, which transformed capitalism from peaceful competition to imperialism. But if capitalism had only now become imperialist, how do we account for the fact that the world had already been divided among the capitalist powers? Grady and Grocott argue that capitalism has always been imperialist. What Lenin called peaceful competition was actually competition among capitalist states to integrate the world’s territory into their expanding economies largely by informal, i.e., peaceful, means. In Lenin’s highest stage of capitalism, competition among capitalist states for economic territory carried on as it always had, except that now it was pursued mainly through violent means, because the peaceful methods of the previous period, the imperialism of free trade as Gallagher and Robinson called it, was either breaking down under the rebellion of subject peoples or was no long suitable for expansion into the territory that remained. In this latter sense, the word “imperialist” becomes synonymous with violent expansion. The important point is that it is not monopoly that makes capitalism imperialist, and it was not monopoly that forced capitalist states to use violence in the service of expansion; instead, imperialism, in the sense of competition among capitalist states for economic territory, is always present in capitalism. The motive, rooted in capitalism itself, doesn’t change; only the methods do. Each capitalist is a threat to every other capitalist, and each capitalist state is a threat to every other capitalist state. To counter the threat, capitalists and capitalist states need to expand the territory over which they have influence and control. The necessity of self-preservation forces them into a competition for economic territory. They use both informal (peaceful) and formal (violent) means of projecting their influence, with a preference, however, for informal control where the circumstances allow.

To some Marxists, then, imperialism means the spread of capitalism to non-capitalist territory as a desirable development; to others, the exploitation of the periphery by the metropole, either as the outcome of a rivalry among capitalist states for economic territory or as a collaboration among capitalist powers in a Kautskyist ultra-imperialism; to still others, imperialism is the struggle among great powers to redivide a world that has already been divided into colonies and spheres of influence. The trouble with arguing, as Desai et al have done, that Russian actions cannot be characterized as imperialist, is that imperialism means different things to different people. In what sense of the word ‘imperialism’ is Russia not imperialist?

At two points in their paper, Desai and her coauthors define imperialism indirectly as a state imposing its capitalists’ will on other territories and populations.

- “It is never impossible that the contradictions of capitalism will lead the Russian state to seek resolutions for them … beyond its borders by using the means at its disposal including its international power.”

- “…the Russian state can be used to impose its capitalists’ will on other territories and populations.”

Thus, imperialism, in this formulation, is the process of a state imposing its will on other territories and populations. Its motive is to protect and expand the interests of its national capitalists beyond the state’s borders. The definition has two parts: A definition proper: The imposition of the will of a state on other territories and populations. And an explanation: States impose their will on other territories and people in response to the needs of their capitalist class. It’s clear from this definition and other points they made that Desai et al viewed imperialism as capitalist driven. They referred to “capitalist drivers of conflict,” of an intimate connection between capitalism and imperialism (“the left has long recognized that capitalism and imperialism have always been intimately linked”), and criticized what they describe as the Schumpeterian view that capitalism does not need imperialism, thereby implying in their criticism that capitalism does, to the contrary, need imperialism.

Desai and her coauthors also indirectly advanced a view of imperialism as a system of rivalry among capitalist states. They argued, contra Kautsky, that “competition between capitalist states never disappears,” and that capitalist states always face the “threat that a rival capitalist power will step up to the plate and take their place.”

Consistent with these arguments, they could have defined imperialism at the outset of their paper as competition among capitalist states to impose their respective wills on other territories and populations in response to the needs of their capitalist class. Having undertaken this basic task, they could have then proceeded to address their main question: Is Russia imperialist? However, had they done this, they would have immediately run into difficulty. If imperialism is competition among capitalist states for economic territory, then the question itself becomes nonsensical. The only question that makes sense within the context of this definition is: Does Russia participate in the system of competition among capitalist states driven by capitalist needs? Since according to Desai et al, “Russia remains capitalist in a meaningful sense,” the obvious answer is yes. All states that are “capitalist in a meaningful sense” must be imperialist since all capitalist states are driven by the inner workings of capitalism to compete for profit-making opportunities anywhere in the world, and all capitalist states are therefore driven to impose their will on foreign territories and populations to secure opportunities for their capitalist class at the expense of other capitalist classes.

Russia’s imposing its will on other territory and peoples in annexing Crimea (and subsequently attempting to impose its will on the remainder of Ukraine by dint of an invasion) meets the trio’s first order definition of imperialism, as the process of a state imposing its will on other territory and populations. Even if the question remains moot as to whether these actions were undertaken in response to the need of Russian capitalists to access Ukraine’s profit-making opportunities at the expense of European and North American capitalists, it remains the case that Russia’s actions in Ukraine are imperialist by the definition Desai et al adopted indirectly of a state imposing its will on foreign territory and populations.

Having developed this line of thought, the trio began quickly to backpedal as they homed in on their main question of whether Russia is imperialist. Where initially they argued that capitalism and imperialism are intimately connected and that capitalism needs imperialism, they shifted tact midway through their paper to argue that imperialism is only a possible outcome of capitalism and not an inevitable one. “It is never impossible that the contradictions of capitalism will lead the Russian state to seek resolutions for them … beyond its borders by using the means at its disposal including its international power,” an awkward way of saying that Russia might act imperialistically, but then again it might not. In effect, they fashioned an escape hatch through which to smuggle Russia from the category of ‘imperialist’— a category to which the Hilferding-Bukharin argument they were developing would inevitably assign Russia.

So, why can Russia not be characterized as imperialist? While Desai et al conceded that Russian is capitalist, that capitalism needs imperialism, and that there is an intimate connection between capitalism and imperialism, they concluded that Russia is not imperialist for the following reasons:

- The EU represents a greater threat to Ukraine sovereignty than does Russia.

- There are domestic political constraints on the “extent to which the Russian state can be used to impose its capitalists’ will on other territories and populations.”

- Western powers are stronger. Compared to the West, Russia’s capacity to undertake foreign adventures is tiny.

- “While Russian capitalists may be inclined to use their state in order to project their power outwards, the ability of the Russian state to perform this role is constrained…both by the large number of other powers of greater or equal economic weight, and by the pull which their capitalists exert in the heart of the Russian economy.”

- Russia’s capitalist holdings abroad are small in comparison to other countries.

Let’s examine each argument in turn.

1) The EU represents a greater threat to Ukraine sovereignty than does Russia. This can be dismissed immediately as irrelevant. The threat posed by the EU to the sovereignty of Ukraine has no bearing on the question of whether Russia also poses a threat to the sovereignty of Ukraine, or the question of whether Russia has encroached on Ukraine’s sovereignty, as it unquestionably did when it annexed Crimea and also did later when it mounted an invasion of Ukraine‘s remaining territory with the intention of establishing a puppet regime.

2) There are domestic political constraints on the “extent to which the Russian state can be used to impose its capitalists’ will on other territories and populations.” There are political domestic and other constraints on the extent to which any capitalist state can be used to impose its capitalists’ will on other territories and populations. Constraints are not unique to Russia, and if they are more numerous or stronger in the case of Russia, without conceding they are, this would represent a difference of degree, not type. The reality that political constraints can affect the actions of the US state does not negate the United States’ imperialist character. Nor should it negate Russia’s. It should also be noted that in pointing to constraints which limit the extent to which the Russian state can be used to act imperialistically, Desai and her coauthors conceded that the Russian state can be used imperialistically. The fact that it had been used imperialistically to annex Crimea, and has since been used to attempt to impose Moscow’s will by means of an invasion on the remaining parts of Ukraine’s territory, demonstrates empirically that what the Russia state can do, it does do.

3) Western powers are stronger. Compared to the West, Russia’s capacity to undertake foreign adventures is tiny. This argument confuses quantity with quality. All states differ in degree. The question is, do they differ in type? Fascist Italy’s capacity to undertake foreign adventures compared to that of the USA and Britain was tiny. That didn’t mean that Fascist Italy wasn’t an imperialist aggressor. Desai et al may just as well have said that pregnant women in their final trimester are much bigger than pregnant women in their first trimester, therefore women in their first trimester are not pregnant.

More to the point, regardless of Russia’s capacity to undertake foreign adventures, it has undertaken foreign adventures, and had at the time Desai et al wrote their paper. It had annexed Crimea. Russia has since demonstrated that its more modest capacity to undertake foreign adventures compared to its Western rivals hasn’t prevented it from undertaking foreign adventures in Ukraine or committing the supreme international crime.

4) While Russian capitalists may be inclined to use their state in order to project their power outwards, various factors prevent this from happening. Again, this totally ignores the reality that despite the constraint on it, the Russian state projected its power outward into Ukraine when it annexed Crimea. Its invasion of the remaining parts of Ukraine is nothing but the projection of Russian power beyond its borders with the aim of imposing Moscow’s will on a foreign territory and population.

5) Russia’s capitalist holdings abroad are small in comparison to other countries. This is a return to the argument that Russia cannot be imperialist, despite its acknowledged capitalist character, despite the acknowledged intimate connection between capitalism and imperialism, and despite the acknowledged inclination of Russian capitalists to use their state to project power outwards, because Russia is a smaller capitalist power than the United States. Again, Fascist Italy and Shintoist Japan were much smaller capitalist powers that the United States and Britain in the 1930s, but few people any more would say that they weren’t imperialist aggressors (although there were people at the time, who did.)

The sum and substance of the Desai et al claim that Russia is not imperialist was this: G7 countries are imperialist. G7 countries are stronger economically and militarily than Russia. Therefore, Russia is not imperialist. In effect, the trio conceptually organized capitalist powers along a scale from the strongest to weakest. They then arbitrarily established a cut-off that divided capitalist states into two classes: imperialist and non-imperialist. The dividing line placed Russia on the non-imperialist side and G7 countries on the other side, or to put it another way, Desai and her coauthors affixed the label ‘imperialist’ to the G7 countries and affixed the label “non-imperialist’ to Russia. This approach broke fundamentally with the Hilferding-Bukharin-Lenin model to which they had earlier paid homage. It did so by creating a category of capitalist states that are non-imperialist—that is, states that are outside the system of rivalry for economic territory that is driven by the capitalist compulsion to accumulate. If capitalism and imperialism are intimately connected, and capitalism needs imperialism, how can a capitalist state not be imperialist? But even if we accept, arguendo, that this break is legitimate, an obvious question arises: At what point does the hill become a mountain? When does Russia become strong enough economically and militarily to pass the imperialist threshold? When would a pregnant woman become pregnant enough for Desai and her coauthors to call her pregnant? “Russia,” they concluded, “has a long way to go to enter the select world league of imperialist robber nations.” But they were silent on the criteria one should use to determine when a state had joined this select group. Refusal to set a target in advance of analysis is the fundamental characteristic of the Texas sharpshooter fallacy. The Texas sharpshooter fires his gun at the side of a barn. He then draws a circle around the bullet holes, and declares the circle the target. This is the crux of the Desai et al argument. They define imperialism post facto to exclude Russia. Thus, they fill 19 pages of print with an argument that reduces to just nine words: Russia is not imperialist because we say it isn’t.

To sum up to this point, Desai et al embarked on a project of deciding whether Russia is imperialist without first defining what they meant by imperialism. At no point did they say either that “This is what we consider imperialism to be,” or that “This is the benchmark against which we’ll judge whether Russia is imperialist.” Instead, while they paid lip service to the thinking of Hilferding, Bukharin, and Lenin, which sees imperialism as intimately connected to capitalism, they introduced a concept foreign to the thinking of these Marxist theorists, namely, that imperialism is only a possible and not an inevitable feature of capitalism. As such, some capitalist countries can be imperialist and others non-imperialist. (In this, they shared the thinking of Karl Kautsky, who viewed imperialism as a policy choice, not a necessary outcome of capitalism.) Their decision as to which capitalist states are not imperialist reduced to: Is the state strong enough to impose its will on other territories and populations? If not, it is not imperialist. Hence, rather than seeing imperialism as a competition among capitalist states for economic territory whose tensions can escalate to war, Desai et al constructed a classification which divides the universe of capitalist states into two categories: large capitalist states, which are labelled imperialist, and smaller ones, which are labelled non-imperialist. Size is important so far as it is correlated with the ability of a state to dominate others. Since large capitalist states are more likely to have the means to impose their will on other states, they are labelled imperialist, while those states which lack this ability are called non-imperialist. But even by this highly restrictive definition of imperialism, Russia must be classified as imperialist. In imposing its will on Ukraine, first by annexing Crimea in 2014, and by launching a general invasion in February 2022, Russia demonstrated that it has the capacity to dominate foreign territory and populations. Therefore, even by the authors’ own highly restrictive definition of imperialism, Russia is imperialist.

While spreading nonsense about Russia, the trio also spent a good deal of time articulating an equally risible view of China. They created a false dichotomy between the neoliberal policies of the West and “China and other emerging economies,” as if China operates at a remove from the US economy and its neoliberal policies. The shift in “the world’s center of gravity away from the West and towards China and other emerging economies” of which Desai and her coauthors wrote, is little more than the integration of China and other low-income countries into G7 economies as low-wage manufacturing centers–what is called the world’s, i.e., the G7’s, factory floor. The “emerging economies” are emerging precisely because they have been integrated into the US-superintended global economy. The communist parties of China and Vietnam act as willing neoliberal collaborators in creating highly attractive investment climates for an almost complete list of the world’s largest Western capitalist enterprises, which are invited to exploit cheap and highly disciplined Eastern labor. That’s not to say that Beijing doesn’t also seek to build an economy that is independent of the G7 countries, but Desai et al completely ignore Beijing’s collaboration in the neoliberalism of the West as an important factor in China’s development. In large measure, the shift in the economic center of gravity from the West to China is nothing more than the logical working out of neoliberal policy. One could wonder on what planet Desai and her coauthors had lived for the past 40 years when they asserted that “China’s economic growth in recent decades is precisely the outcome of a consistent refusal to accommodate the Washington Consensus.” On the contrary, China’s economic growth in recent decades is precisely the outcome of a consistent willingness by Beijing to collude in the demotion of China’s land, labor, and markets to a means of gratifying the avarice of the West’s largest capitalist enterprises.

Had Desai et al an ulterior motive for arguing, against even their own very restricted post facto definition of imperialism, that Russian is not imperialist? The authors said they deplored characterizations of Russia as an imperialist aggressor because the description dovetailed “nicely with Western demonization of the Putin regime.” Their concern, they said, was that these characterizations would give “theoretical dignity to the ambitions of US-policy makers.” Yet the question of whether their analysis would give comfort to the US bourgeoisie or the Russian bourgeoisie should have awakened no apprehension in Marxist scholars whose principal concern should have been the class interests of the proletariat. What’s more, in openly deploring one possible answer to the question of whether Russia is imperialist, they, themselves, raised the question of whether political considerations guided their analysis. The evidence suggests that Desai and her coauthors entered the arena of debate, not with the intention of understanding the world as it is so it can be changed to the benefit of the proletariat, but to present an understanding of the world that dovetailed nicely with Russia’s denial of its imperialist aims and gave theoretical dignity to the ambitions of Russian-policy makers, i.e., as court philosophers of the Kremlin. In light of the authors’ admitted leanings toward Moscow in its conflict with Washington, the answer to the question posed above about how high they would set the threshold for admitting Russia into the world league of imperialist states is high enough that Russia would never enter. Indeed, we can imagine that the criteria for entry, in the hands of Desai et al, would unremittingly shift to exclude Russia as circumstances dictated. To do otherwise, would be to create a characterization of Russia that would dovetail nicely with Western vilification of the country, an outcome the court philosophers explicitly indicated they wanted to avoid. If George H. W. Bush would never apologize for America, then Desai and her colleagues will never apologize for Russia. This, along with their relying on the Texas sharpshooter fallacy to make the case that Russia isn’t imperialist, shows their analysis to be an exercise in political perjury, not Marxist scholarship. The court philosophers’ preference was to limit condemnation to Washington rather than to the bourgeois order or the capitalism of which imperialism is the necessary consequence. Not only did they absolve Russia of imperialist guilt, they absolved capitalism of imperialist guilt, describing imperialism as only a possible and not an inevitable outcome of capitalism. They are not scholars, much less Marxist ones, but merely political prize fighters for the Russian capitalist class and the bourgeois order of which it is a part.

There are four conclusions the authors might, whether by design or accident, have us draw from their pro-Moscow, pro-bourgeois argument.

- The historical mission of the proletariat is not to bring forward the new socialist society with which the old bourgeois order is pregnant, but to support weaker bourgeois states that fight the stronger US bourgeoisie.

- The enemy of the proletariat is not the bourgeoisie that enslaves and exploits it, but only the largest bourgeoisie, the ones with the greatest foreign capital holdings, or more specifically, foreign capital holdings greater than those of Russia and China.

- The task of the proletariat is to side with any weaker bourgeoisie that fights the stronger US bourgeoisie.

- The proletariat should celebrate its enslavement and exploitation so long as the enslavers’ headquarters is not Wall Street, Frankfurt, Tokyo, Paris, or London.

The pro-Russia intelligentsia, so committed to invoking Lenin as grounds for mobilizing support for Russia in Moscow’s struggle with the United States over Ukraine, is deaf to Lenin’s dictum: “It is not the business of socialists to help the younger and stronger robber to rob the older and fatter bandits, but the socialists must utilize the struggle between the bandits to overthrow all of them.” [15] Desai et al would likely agree with this, but not before arbitrarily excluding Russia from the list of bandits, ipse dixit.

The US hegemony of today was preceded by an Anglo-American hegemony, the latter of which aroused the enmity and moral indignation of the Axis powers, the emerging capitalist states of their day. The Axis states complained bitterly that the United States and Britain, through their vast control of the world’s resources and markets, hindered the economic development of the Axis powers, denying the peoples of Middle Europe, the Mediterranean, and the East their day in the sun. Intellectuals who supported the Axis project, spoke of the necessity of liberating humanity from Anglo-American domination. Exponents of multipolarity today, Desai and Freeman among them, are the modern equivalent of the Western intellectuals who argued that rather than competing with Germany, Italy, and Japan, Washington and London should allow the Axis powers to establish their own regional hegemonies. This was advocacy of a Kautsky-style ultra-imperialist division of the world into a series of regional empires, a new multipolarity.

Advocates of multipolarity fight, not for the end of hegemony, but for the end of US efforts to prevent Russia and China from expanding their regional empires—hence, for the end of US world hegemony and the emergence of Russian and Chinese regional hegemonies. Multipolarity is an imperialist project, even if its advocates use anti-imperialist rhetoric and themes to cloak its true identity. This is not to say that US hegemony is more desirable than a multipolar series of regional hegemonies, only that imperialism in any form, multipolar or unipolar, is equally objectionable and equally inimical to the class interests of the proletariat. Would the international working class of the 1930s have been better off in a multipolar world in which London, Paris, and Washington ceded Central and Eastern Europe to Germany, the Balkans to Italy, and East Asia and the Pacific to Japan? For Marxists, the key question is not whether three capitalist centers should divide the world amongst themselves—the United States, China, and Russia, in preference to only one, the United States. Is enslavement and exploitation by Chinese and Russian capitalists more desirable than enslavement and exploitation by US capitalists? The key task is to bring the enslavement and exploitation of the proletariat by the bourgeoisie, regardless of the exploiters’ nationality, to an end. The job of socialists, according to Lenin, is to end war by ending the division of humanity by class and nation. That won’t be accomplished by exercises in political perjury, where the nature of Russia as an imperialist aggressor is covered up by intellectuals who think Marxism is rooting for the weaker bourgeoisie in an inter-imperialist conflict.

1. Radhika Desai, Alan Freeman & Boris Kagarlitsky (2016) “The Conflict in Ukraine and Contemporary Imperialism,” International Critical Thought, 6:4, 489-512,

2. Karl Marx, “The British Rule in India,” in James Ledbetter, ed., Dispatches for the New York Tribune: Selected Journalism of Karl Marx, Penguin Books, 2007, p.219.

3. Bill Warren, Imperialism: Pioneer of Capitalism, Verso, 1985, p. 49.

4. John Weeks, “Imperialism and World Market,” in Tom Bottomore, ed., A Dictionary of Marxist Thought, Blackwell Publishing, 1991, pp. 252-256.

5. Ibid.

6. Anthony Brewer, Marxist Theories of Imperialism: A Critical Study, Routledge, 1990, p. 130.

7. Joseph Stalin, Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR, “Chapter 6, Inevitability of Wars Between Capitalist Countries,” 1952. Stalin wrote, “Outwardly, everything would seem to be “going well”: the U.S.A. has put Western Europe, Japan and other capitalist countries on rations; Germany (Western), Britain, France, Italy and Japan have fallen into the clutches of the U.S.A. and are meekly obeying its commands. But it would be mistaken to think that things can continue to ‘go well’ for ‘all eternity,’ that these countries will tolerate the domination and oppression of the United States endlessly, that they will not endeavor to tear loose from American bondage and take the path of independent development.”

8. Brewer, p. 130.

9. Weeks, p. 252.

10. V.I. Lenin, Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism, International Publishers, 1939, p. 91-92.

11. V.I. Lenin, “Conference of the Foreign Sections of the R.S.–D.L.P.” in Collected Works of V.I. Lenin Volume XVIII: The Imperialist War, International Publishers, 1930, pp. 145-146.

12. John Gallagher and Ronald Robinson, “The Imperialism of Free Trade,” The Economic History Review, New Series, Vol. 6, No. 1 (1953), pp. 1-15.

13. John Gallagher and Ronald Robinson, Africa and the Victorians: The Official Mind of Imperialism, MacMillan Press, 1983.

14. Jo Grady and Chris Grocott, eds. The Continuing Imperialism of Free Trade: Developments, Trends and the Role of Supranational Agents, Routledge, 2020.

15. V.I. Lenin, “Socialism and War” in Collected Works of V.I. Lenin Volume XVIII: The Imperialist War, International Publishers, 1930, pp. 223-224.